Here is a deep dive into the Flores settlement that currently governs what the government must, may, and may not do with migrant children.Here's an explainer from Vox that gives a more detailed explanation of why Trump's new executive order probably won't survive a legal challenge. It also explains that it's far beyond the government's current capabilities and capacities to humanely house all of the families who'd be affected.

Everything flows from Trump's zero tolerance policy. If you're going to criminally prosecute everyone who enters without authorization, then you either have to take away their children, or you have to lock them all up together. I doubt that a federal judge would allow the Trump administration to do the latter, particularly in the slapdash and plainly inadequate circumstances that now exist. If so, Trump would have to either continue separating thousands of children (some of them permanently), or he'd have to discontinue the zero tolerance policy. I think that people in his administration know all of this (even if he doesn't), which causes me to regard this new executive order as just another cynically dishonest move by the Sociopath-in-Chief.

Colleges

- American Athletic

- Atlantic Coast

- Big 12

- Big East

- Big Ten

- Colonial

- Conference USA

- Independents (FBS)

- Junior College

- Mountain West

- Northeast

- Pac-12

- Patriot League

- Pioneer League

- Southeastern

- Sun Belt

- Army

- Charlotte

- East Carolina

- Florida Atlantic

- Memphis

- Navy

- North Texas

- Rice

- South Florida

- Temple

- Tulane

- Tulsa

- UAB

- UTSA

- Boston College

- California

- Clemson

- Duke

- Florida State

- Georgia Tech

- Louisville

- Miami (FL)

- North Carolina

- North Carolina State

- Pittsburgh

- Southern Methodist

- Stanford

- Syracuse

- Virginia

- Virginia Tech

- Wake Forest

- Arizona

- Arizona State

- Baylor

- Brigham Young

- Cincinnati

- Colorado

- Houston

- Iowa State

- Kansas

- Kansas State

- Oklahoma State

- TCU

- Texas Tech

- UCF

- Utah

- West Virginia

- Illinois

- Indiana

- Iowa

- Maryland

- Michigan

- Michigan State

- Minnesota

- Nebraska

- Northwestern

- Ohio State

- Oregon

- Penn State

- Purdue

- Rutgers

- UCLA

- USC

- Washington

- Wisconsin

High Schools

- Illinois HS Sports

- Indiana HS Sports

- Iowa HS Sports

- Kansas HS Sports

- Michigan HS Sports

- Minnesota HS Sports

- Missouri HS Sports

- Nebraska HS Sports

- Oklahoma HS Sports

- Texas HS Hoops

- Texas HS Sports

- Wisconsin HS Sports

- Cincinnati HS Sports

- Delaware

- Maryland HS Sports

- New Jersey HS Hoops

- New Jersey HS Sports

- NYC HS Hoops

- Ohio HS Sports

- Pennsylvania HS Sports

- Virginia HS Sports

- West Virginia HS Sports

ADVERTISEMENT

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Trump is holding children hostage

- Thread starter Rockfish1

- Start date

Here's an explainer from Vox that gives a more detailed explanation of why Trump's new executive order probably won't survive a legal challenge. It also explains that it's far beyond the government's current capabilities and capacities to humanely house all of the families who'd be affected.

Everything flows from Trump's zero tolerance policy. If you're going to criminally prosecute everyone who enters without authorization, then you either have to take away their children, or you have to lock them all up together. I doubt that a federal judge would allow the Trump administration to do the latter, particularly in the slapdash and plainly inadequate circumstances that now exist. If so, Trump would have to either continue separating thousands of children (some of them permanently), or he'd have to discontinue the zero tolerance policy. I think that people in his administration know all of this (even if he doesn't), which causes me to regard this new executive order as just another cynically dishonest move by the Sociopath-in-Chief.

I can’t wait for a republican to sue Trump over this. We all know how republicans feel about executive orders.

This is the reason we need a stand alone bill to pass thru Congress. This executive order will not survive in court and the administration is not going to go back to "catch and release". So without legislation we are right back in the same place.Here's an explainer from Vox that gives a more detailed explanation of why Trump's new executive order probably won't survive a legal challenge. It also explains that it's far beyond the government's current capabilities and capacities to humanely house all of the families who'd be affected.

Everything flows from Trump's zero tolerance policy. If you're going to criminally prosecute everyone who enters without authorization, then you either have to take away their children, or you have to lock them all up together. I doubt that a federal judge would allow the Trump administration to do the latter, particularly in the slapdash and plainly inadequate circumstances that now exist. If so, Trump would have to either continue separating thousands of children (some of them permanently), or he'd have to discontinue the zero tolerance policy. I think that people in his administration know all of this (even if he doesn't), which causes me to regard this new executive order as just another cynically dishonest move by the Sociopath-in-Chief.

A person who genuinely cared about the humane implementation of a zero tolerance policy would first create the necessary infrastructure (laws, facilities, people, capabilities), then implement the policy. It would be an enormous undertaking. This is among the reasons we haven't ever done it.This is the reason we need a stand alone bill to pass thru Congress. This executive order will not survive in court and the administration is not going to go back to "catch and release". So without legislation we are right back in the same place.

But no decent person would purposely adopt a cruel policy that terrorizes children to get leverage for maximalist goals. That's the hostage-taking approach you support.

Here's an explainer from Vox that gives a more detailed explanation of why Trump's new executive order probably won't survive a legal challenge. It also explains that it's far beyond the government's current capabilities and capacities to humanely house all of the families who'd be affected.

Everything flows from Trump's zero tolerance policy. If you're going to criminally prosecute everyone who enters without authorization, then you either have to take away their children, or you have to lock them all up together. I doubt that a federal judge would allow the Trump administration to do the latter, particularly in the slapdash and plainly inadequate circumstances that now exist. If so, Trump would have to either continue separating thousands of children (some of them permanently), or he'd have to discontinue the zero tolerance policy. I think that people in his administration know all of this (even if he doesn't), which causes me to regard this new executive order as just another cynically dishonest move by the Sociopath-in-Chief.

I don't know but I'm guessing most trump supporters still have one.What's a VCR?

The poor man cant catch a break.... flies all the way out here/Singapore to sign basically a MOU to help the world and now this:

I have a feeling we won't see the Trump name on the list of possible Nobel prize winners this year -- though I wouldn't be surprised to see framed photoshopped images appear next to those Time Magazine covers.

I have a feeling we won't see the Trump name on the list of possible Nobel prize winners this year -- though I wouldn't be surprised to see framed photoshopped images appear next to those Time Magazine covers.

I don't know but I'm guessing most trump supporters still have one.

I am guessing more likely Betamax and still fight the good fight.

God, I am no Spelling Nazi but one would expect more from your elected officials:

I would assume it was written by a lawyer?

Not just any lawyer, one of the best lawyers.

That’s it, VPM, justify the terrorizing of children. It’s your boy doing, so you gotta make it ok in your mind.

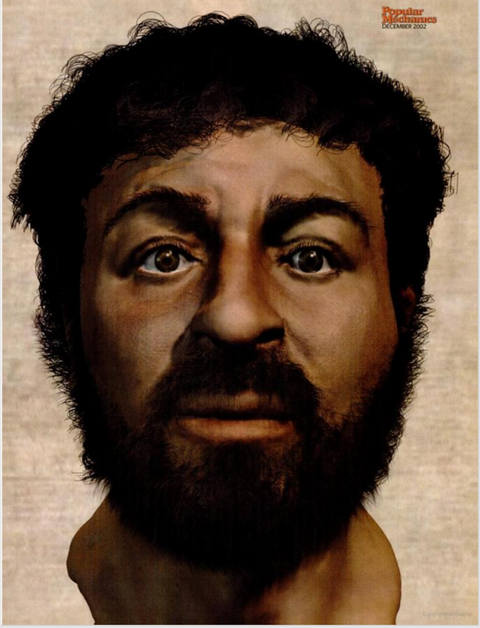

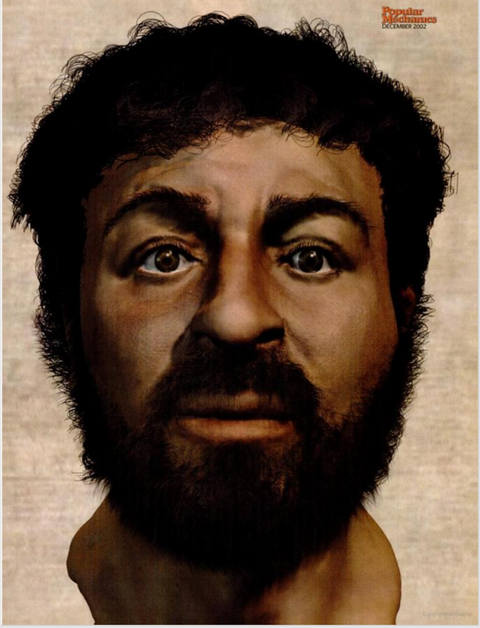

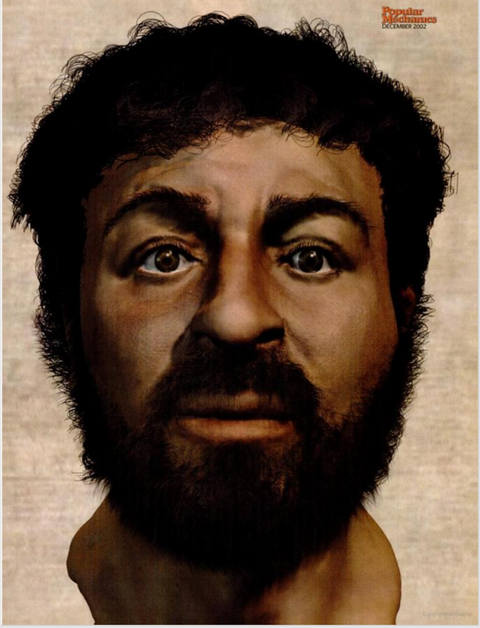

This sure changes things. Is there any doubt Jesus committed an illegal act against Sanhedrin authority and deserved to stand trial?

He still might be in the running for an Ig Nobel prize. While I realize it is normally trivial scientific reasearch that takes home the Iggy, i believe he still has a chance. His work in the areas of cruel, evil and stupid are unmatched. While technically not a scientist, researcher, businessman or decent human being; his accomplishments can't be overlooked.The poor man cant catch a break.... flies all the way out here/Singapore to sign basically a MOU to help the world and now this:

I have a feeling we won't see the Trump name on the list of possible Nobel prize winners this year -- though I wouldn't be surprised to see framed photoshopped images appear next to those Time Magazine covers.

Separating children from their parents

Disrespecting:

- a war hero

- A Mexican American judge

- A Gold Star Family

- LGBTQ soldiers (hell all of them)

- Our allies

Praising:

- a Korean dictator

- a Russian dictator

- a Turkish dictator

- Good klan members

If that doesn't have Iggy written all over i don't know what does.

Why are you showing a picture of a long-haired bearded hippie alongside a quote by Jesus?Aren't you supposed to at least act like you follow a God who would say:

Last edited:

Why are you showing a picture of a long haired bearded hippie alongside a quote by Jesus?

Lots of people here get ill when anyone points out that Jesus was certainly not white.

They would certainly cross the street if they saw this guy coming:

Not sure VPN will have this at his altar. Might be the beard but also other features.

I support a stand-alone bill so that they don't have to separate families. Not sure how you equate that with "hostage-taking".A person who genuinely cared about the humane implementation of a zero tolerance policy would first create the necessary infrastructure (laws, facilities, people, capabilities), then implement the policy. It would be an enormous undertaking. This is among the reasons we haven't ever done it.

But no decent person would purposely adopt a cruel policy that terrorizes children to get leverage for maximalist goals. That's the hostage-taking approach you support.

The stand-alone bill would lock children up with their parents in conditions most non-sociopaths regard as deplorable. It would also endorse Trump’s zero tolerance policy. Trump believed he’d never get Democrats on board with this unless he held children hostage. Thus he created this crisis to get what he wanted. You’re okay with that. Parroting “stand-alone bill” changes nothing.I support a stand-alone bill so that they don't have to separate families. Not sure how you equate that with "hostage-taking".

Bruce1, you never responded to my post about the holocaust survivor who said the most traumatic part of all was when he was separated from his mother.I heard a report from a pediatrician today who said because the kids weren't talking much it was a sign the were traumatized from being taken from their parents. That is interesting since these kids just trekked over 2000 miles and prior to that lived in fear and abject poverty for the prior years of their lives.

Also, your post says "a pediatrician". But the pediatrician who is speaking is not just some pediatrician, it is Colleen Kraft the president of the American Academy of Pediatricians. She is talking in a very clear and rational way. She is talking about the science of stress. She is saying that the research shows that this causes long lasting harm.

To summarize....

The Trump child concentration camps will remain open and unchanged for those that are already in them.

In the future, children will be jailed within the same concentration camp as their parents.

The rules to limit the children's time in the concentration camps to 20 days are requested to be waived, so that both children and parents can be detained in the concentration camps as long as is necessary, from both a political and legal perspective.

Do I have this right?

The Trump child concentration camps will remain open and unchanged for those that are already in them.

In the future, children will be jailed within the same concentration camp as their parents.

The rules to limit the children's time in the concentration camps to 20 days are requested to be waived, so that both children and parents can be detained in the concentration camps as long as is necessary, from both a political and legal perspective.

Do I have this right?

I don't see the administration going back to catch and release. They are going to be detained. They are either going to be detained as a family or separately. I prefer as a family.The stand-alone bill would lock children up with their parents in conditions most non-sociopaths regard as deplorable. It would also endorse Trump’s zero tolerance policy. Trump believed he’d never get Democrats on board with this unless he held children hostage. Thus he created this crisis to get what he wanted. You’re okay with that. Parroting “stand-alone bill” changes nothing.

Hence the hostage-taking.I don't see the administration going back to catch and release. They are going to be detained. They are either going to be detained as a family or separately. I prefer as a family.

In your opinion, should they be detained?Hence the hostage-taking.

You’re looking at it from an American point of view- here you can almost always leave the situation and be OK. In the Central American countries, this really isn’t an option.

What about gang violence? If the government is powerless to stop it (or domestic abuse), why shouldn’t that qualify for asylum? Where the hell else can they go? Mexico is largely lawless as well, in huge swaths of the country.

Session’s guidance on this topic is inhuman. There’s a reason why his own church denomination has denounced him.

I’ll neber understand turning a blind eye to fellow humans in need. Again, these folks aren’t coming here with their kids for economic opportunity- despite what the right wing media wants to promote. They’re at the border because they’ve got no other options.

You playing the morality card isnt persuasive. We have an established process for asylum seekers. I’m good with that.

You seem to think we can fix crime and danger in foreign countries with our immigration policy—make that by disregarding immigration policy. I don’t think so. That isn’t to say I don’t have sympathy for the troubled people throughout the world. I have sympathy for posters here who have had setbacks and health issues. But sympathy is no response. This isn’t just a US problem. Migrants away from rural or backwards parts of the world have inundated many places that can’t handle the influx. That doesn’t help anybody.

I mostly have no problem with legal immigration. But the illegals come here in a deliberate illegal fashion and start by not respecting our system. The reason we have this mess about detention is because 90% the illegals who claim asylum after illegal entry give us the finger and don’t show up for asylum hearings. We need to get our own house in order, then we can deal with the rest of the world.

Bruce1, you never responded to my post about the holocaust survivor who said the most traumatic part of all was when he was separated from his mother.

Also, your post says "a pediatrician". But the pediatrician who is speaking is not just some pediatrician, it is Colleen Kraft the president of the American Academy of Pediatricians. She is talking in a very clear and rational way. She is talking about the science of stress. She is saying that the research shows that this causes long lasting harm.

I watched the vid several times. She said the effects can cause long lasting harm. The point I was trying to make was that this Dr is looking at this point in time and has no reference to what these kids have gone thru earlier. I have lived and worked in third world countries. It is heartbreaking to see the world outside of the US but it is ludricous to think that we can solve all of the issues. True, we can do a much better job on the border but to politicize this on either side is wrong. I’m glad Pres Trump signed the order.

It seems what Bruce is saying is that unless you believe in separating infants from their parents in the name of God, you are not much of a Christian. Right, Bruce?Life-long (50+ years) church-going Methodist.

What was your point?

I am glad that you are glad that Trump signed the order. However, the questions remain.I watched the vid several times. She said the effects can cause long lasting harm. The point I was trying to make was that this Dr is looking at this point in time and has no reference to what these kids have gone thru earlier. I have lived and worked in third world countries. It is heartbreaking to see the world outside of the US but it is ludricous to think that we can solve all of the issues. True, we can do a much better job on the border but to politicize this on either side is wrong. I’m glad Pres Trump signed the order.

1) You were in favor of the separation of the children from their parents. If I am not mistaken, you applauded the move. Why have you changed your mind?

2) Trump ordered to separate the children from their parents. Why did he change his mind?

As the story about the holocaust survivor illustrated, the loss of parents is among the worst trauma a child can go through. That one is on us. It is the President who has politicized this issue by INTENTIONALLY choosing a policy he knew would be incendiary. He did it with complete indifference with respect to its effect on the children and families because he thought it would polarize the electorate in ways that benefit him. The President and the GOP intentionally violate core values wrt treatment of immigrant children or torturing prisoners or police violence against minorities because it polarizes the electorate in ways that help them. Liberals are outraged by the violations of care/harm and fairness. But conservatives respond more to the in-group loyalty and respect for authority. Trump and the GOP political class are depraved...as is obvious to anyone with eyes to see.I watched the vid several times. She said the effects can cause long lasting harm. The point I was trying to make was that this Dr is looking at this point in time and has no reference to what these kids have gone thru earlier. I have lived and worked in third world countries. It is heartbreaking to see the world outside of the US but it is ludricous to think that we can solve all of the issues. True, we can do a much better job on the border but to politicize this on either side is wrong. I’m glad Pres Trump signed the order.

Liberals are outraged by the violations of care/harm and fairness. But conservatives respond more to the in-group loyalty and respect for authority.

Wrong. Again, you do not get to define fair. We have a system in place that sets out how you apply for asylum and how you immigrate to this country. There are people who have literally waited years to get into this country legally. A fair process does not give preference to someone who ignores those set rules and walks into the country and in effect line jumps those people who have been waiting for years. And they can do this based not on them being in a worse situation or more needy, nope, simple geography. You are not being fair, you are being led around by emotional squirrels. Those people are nearby so their photos are more readily available to you. People in Sudan getting hacked up by Islamist armies are not front and center so they get ignored (much like these people were ignored from 2009 to 2014, because it was convenient to do so for those trying to manipulate you).

Lots of people here get ill when anyone points out that Jesus was certainly not white.

They would certainly cross the street if they saw this guy coming:

They’d probably get nervous if Jesus got on a plane with them

I am not trying to define fair differently than you. I appreciate your definition of fairness in terms of procedure. I agree that is an aspect of fairness. Judging myself by how I behave when people try to cut in line I myself care a great deal about such notions of fairness. Haidt claims, and I agree, that both liberals and conservatives care about fairness...procedural and outcomes. But what distinguishes liberals and conservatives is that conservatives contextualize fairness with other values like in-group loyalty and respect for authority. For liberals everyone is entitled to fair treatment whether a member of an in-group or not; whether high in the social hierarchy or not. For conservatives in-group loyalty can trump (haha) fairness. Haidt would say that both liberals and conservatives are being led by their emotions. Their ethical emotions are different so they end up with different reactions.Wrong. Again, you do not get to define fair. We have a system in place that sets out how you apply for asylum and how you immigrate to this country. There are people who have literally waited years to get into this country legally. A fair process does not give preference to someone who ignores those set rules and walks into the country and in effect line jumps those people who have been waiting for years. And they can do this based not on them being in a worse situation or more needy, nope, simple geography. You are not being fair, you are being led around by emotional squirrels. Those people are nearby so their photos are more readily available to you. People in Sudan getting hacked up by Islamist armies are not front and center so they get ignored (much like these people were ignored from 2009 to 2014, because it was convenient to do so for those trying to manipulate you).

Stupid flaming post, Meridian. I will pray for you.It seems what Bruce is saying is that unless you believe in separating infants from their parents in the name of God, you are not much of a Christian. Right, Bruce?

Stupid flaming post, Meridian. I will pray for you.

Keep your soiled version of Christianity and its prayers to yourself please. Aren’t you all running low on prayers anyways? After the truckloads of thoughts and prayers that were delivered to the dead children and their grieving parents after all the school shootings we’ve had. You guys were always running low on thoughts. Some of those trucks only had prayers in them.

No, No! Please don't pray for me! I don't want to go to your Haven when I die. I want to go where Jesus is.Stupid flaming post, Meridian. I will pray for you.

It is disgusting and wrong to equate human beings with insects and animals, as Trump so disgracefully does. Illegal immigrants are committing no moral wrong. They are doing what we might do in their place—as we, by defending borders, are doing what they would do if they were in ours. Like so many human institutions, borders are both arbitrary and indispensable. Without them, there are no nations. Without nations, there can be no democracy and no liberalism. John Lennon may imagine that without nations there will be only humanity. More likely, without nations there will only be tribes.

Writing in The Atlantic a year ago, my colleague Peter Beinart remarked on the increasingly unanimous opposition among Democrats to any form of immigration enforcement at all. “An undocumented alien is not a criminal,” Senator Kamala Harris protested last year. That view has been turbocharged over the past week. Here’s how the MSNBC host Chris Hayes described his reaction to a first-person account from a woman who had crossed the border illegally with her child, from whom she had then been forcibly separated:

I was thinking to myself, this reads like the literature of a totalitarian government. This reads like a first-person dispatch from an authoritarian state. This reads like something from a sci-fi novel about some dystopic future.

One of the themes that emerges in that kind of literature is a kind of bureaucratic state that's faceless and incomprehensible. The idea of these kind of like these men with suits or men in uniform who show up and they wield this completely arbitrary power that can crush someone’s life. That goes back to The Trial of Joseph K. by Kafka, and it’s an emerging theme in a lot of the Soviet literature about the experience of the Soviet state that was just completely arbitrary and capricious. It shows up in 1984, just this idea that you’re living your life, you’re doing something, and then all of a sudden, the state can come in and wrench your life apart, and completely [upend] it.

There’s a knock at the door. There’s a call that comes in. There’s a person who gets out of a car and calls your name, and the next thing you know, you’re in handcuffs. That idea of tyranny hanging over people, kind of absurdist tyranny is a really through lining when we think about the kind of societies that we aren’t, non-free societies, societies under the sway of totalitarian regimes, authoritarian regimes, dictatorships, et cetera.

Now notice something: As Hayes elaborates his horror at the separation of mother from child, he seems to arrive at a conclusion that there is something inherently oppressive about any kind of immigration rule at all. The “men in suits or men in uniform” he speaks of do not just “show up.” The border crosser goes to them. She is not just “living her life … and then all of a sudden, the state can come in and wrench your life apart.” She, of her own volition, traveled hundreds of miles to challenge the authority of a foreign state to police its frontiers. When her challenge failed—when she was apprehended and detained—what happened next must have felt harsh and frightening. But dictatorial? Totalitarian? In democracies, too, the wrong side of the law is an inescapably uncomfortable place to find yourself.

https://www.theatlantic.com/politics/archive/2018/06/need-for-immigration-control/563261/

I will gladly admit that "my side" went to the extreme in following the law and separating children from parents. What I would like is for some of you to realize that you took the other extreme position whenever any effort was made to arrive at a compromise on this issue. Frum takes all of us to task in the article.

I very seriously doubt that many, if any, here care that Jesus wasn’t very white.Lots of people here get ill when anyone points out that Jesus was certainly not white.

They would certainly cross the street if they saw this guy coming:

This is a pretty weird jacket to wear.

It's not first ladies don't have a staff who might say "uhhh, are you sure you want to wear that?" I suspect most of them have help picking out their attire historically.

Fox should be all over it. We all know how bent out of shape Fox and their viewers get over wardrobes. Or maybe it’s just tan stuff.

Similar threads

- Replies

- 0

- Views

- 134

- Replies

- 33

- Views

- 2K

- Replies

- 55

- Views

- 1K

- Replies

- 33

- Views

- 737

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT