America’s Factory Towns, Once Solidly Blue, Are Now a GOP Haven

A generation ago, Democrats represented much of the country’s manufacturing base. Now, it’s in GOP hands, a swing remaking both parties

Wayne Wright keeps the fabric flowing at the Harris textile plant owned Greenwood Mills in Greenwood, S.C. DANIELLE PAUL FOR THE WALL STREET JOURNAL

By Bob Davis and Dante Chinni

July 19, 2018 11:16 a.m. ET

WASHINGTON—The Republican Party has become the party of blue-collar America.

After the 1992 election, 15 of the 20 most manufacturing-intensive Congressional districts in America were represented by Democrats. Today, all 20 are held by Republicans.

The shift of manufacturing from a Democratic stronghold to a Republican one is a major force remaking the two parties. It helps explain Donald Trump’s political success, the rise of Republican protectionism and the nation’s polarized politics. It will help shape this year’s midterm elections.

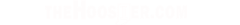

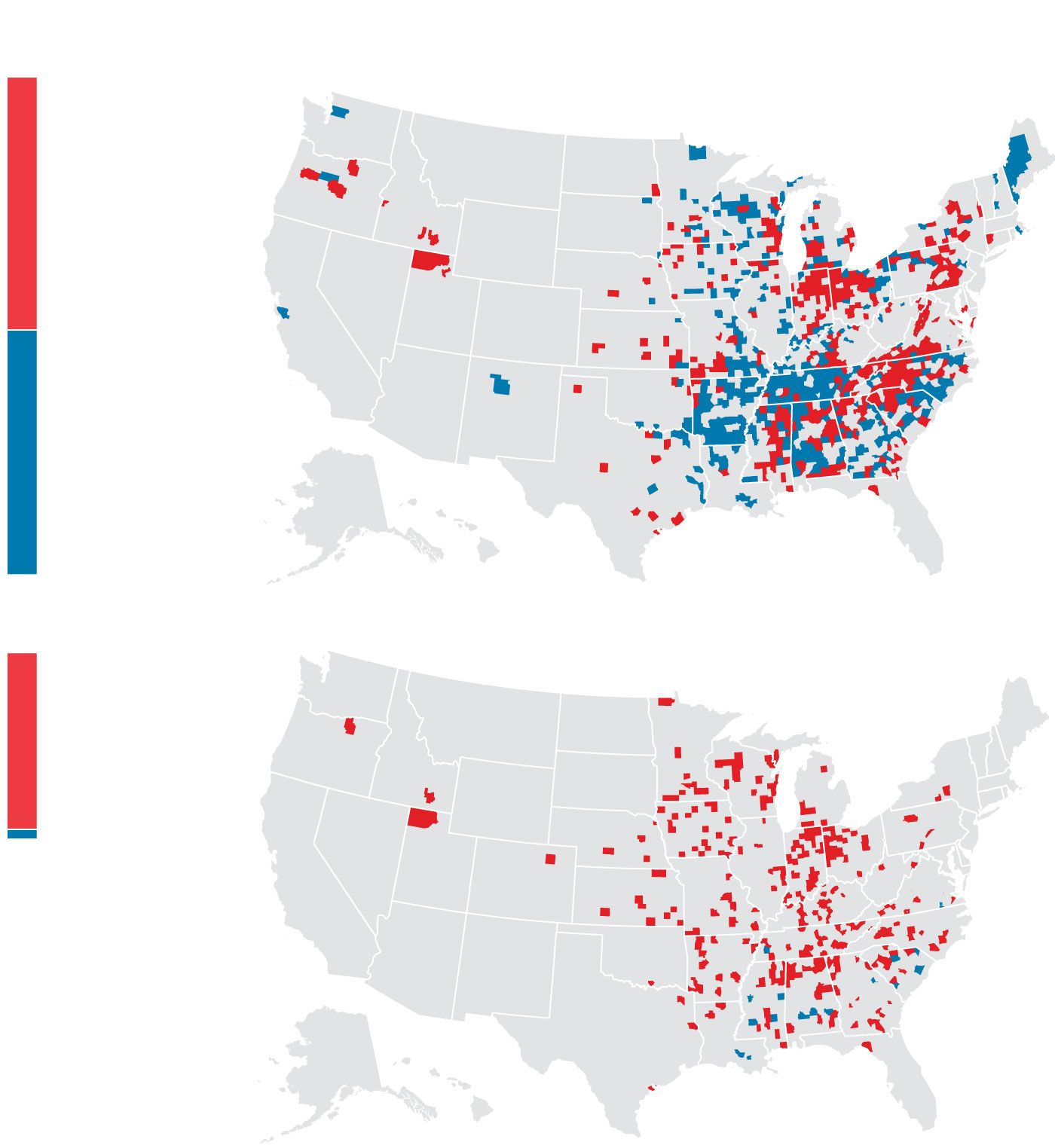

Conservative Takeover

In the 1992 presidential election, manufacturing-intensive counties split pretty evenly between the Democratic and Republican contenders. By 2016, nearly all those counties voted Republican.

Counties where manufacturing is at least 25% of all jobs, by election result

1992

438 Counties that went for George H.W. Bush

424 Counties that went for Bill Clinton

2016

306 Counties that went for Donald Trump

17 Counties that went for Hillary Clinton

Sources: Brookings Institution (manufacturing); Dave Leip's Atlas of U.S. Presidential Elections; University of Colorado Boulder’s Congressional District Data File (election results)

South Carolina’s third Congressional district, on the edge of the Blue Ridge Mountains, epitomizes the swing from blue to red.

In 1992, the district was dotted with textile mills and was represented by a Democrat, Butler Derrick, as it had been for the prior 17 years. He backed gun control, got along with unions and voted for a 1986 law granting citizenship to millions of illegal immigrants.

The district has since become an auto-parts and plastics manufacturing center. Then and now it was among the 20 districts in the nation with the highest concentration of workers in the manufacturing sector, according to a Wall Street Journal analysis of census data.

Today, the district is represented by a Republican, Jeff Duncan. He has compared illegal immigrants to “any kind of vagrant or animal,” gets a 5% rating by the AFL-CIO and derides the World Trade Organization as a “globalist organization” with too much power.

“We’re in servitude” to Chinese bond buyers and other creditors, he told a constituent during a teleconference with voters in May.

Greenwood Mills’ Harris plant produces undyed cloth from bales of cotton and nylon. At the bottom right, Ginger Strawhorn checks the cloth for imperfections. PHOTOS: DANIELLE PAUL FOR THE WALL STREET JOURNAL(3)

The Republican Party didn’t have a grand strategy to capture manufacturing. It happened over time as the economy and party changed.

Many counties that leaned toward Democrats lost so many factory jobs during the past 25 years that they ceased being manufacturing centers.

As the U.S. factory workforce diminished in size—from 15.4% of the U.S. workforce in 1992 to 8.5% today—it moved out of big cities that were union strongholds and into blue-collar suburbs.

Declining SectorManufacturing as a percentage of all jobsSource: Labor Department via the Federal ReserveBank of St. Louis

%1990’952000’05’10’150246810121416

The Northeast and New England, strongholds for Democrats, largely disappeared from the map of manufacturing-intensive counties, according to an analysis for the Journal by the Brookings Institution’s metropolitan policy program. There are no manufacturing-intensive counties any longer in Massachusetts or Connecticut.

Pittsburgh, another Democratic bastion, shed its Steel City heritage and became a university and health-care center. Manufacturing jobs declined by 37,000 in the metropolitan area since 1992, while the number of service-industries employees increased by 168,000.

The new manufacturing heartland runs through areas outside suburbs along interstate highways south from Michigan, Minnesota and Wisconsin through Ohio and into the Carolinas and the deep South.

There, whites without a college education, who identified with the Republican Party’s focus on social issues and abortion restrictions, took up many of the factory jobs. The Trump administration’s tough stance on trade deepened the bonds with workers who believed they were hurt by free-trade deals.

“Manufacturing moved to where the Republican party has been building strength,” says Jonathan Rodden, a Stanford University political scientist, who studies the geography of political change.

Other manufacturing areas have flipped to vote for Republicans. In 1992, there were 860 counties where at least 25% of the working population was employed in manufacturing. Democrat Bill Clinton won 49% of those counties. By 2016, manufacturers employed at least a quarter of the workforce in only 320 counties. Ninety-five percent of them went for Donald Trump.

Hartzell Propeller Inc. in Piqua, Ohio, manufactures propellers for aircrafts. Baline Collins, top, is a new hire. Jeff Newnam, lower right, has worked at the company for 37 years. PHOTOS: ANDREW SPEAR FOR THE WALL STREET JOURNAL(3)

In Wisconsin, five manufacturing-intensive counties in the northwest of the state have flipped from Democrats to Republicans since 1992. Three of those counties went for Mr. Trump in 2016 by margins of more than 25 percentage points.

Labor unions, which have long allied with Democrats, now represent just 9% of manufacturing workers, down from 20% in 1992, according to Barry Hirsch, an economist at Georgia State University.

“My image of Republicans is of a blue-collar type,” says Larry Smith, a 68-year-old weave room supervisor at Greenwood Mills Inc. in South Carolina’s third Congressional District. He voted for Democrats before, including Barack Obama in 2008, but sided with Mr. Trump in 2016. “Democrats come from more financially successful groups.”

His boss, Jay Self, says a lot of local voters were turned off to the Democratic Party when Bill Clinton eased the entry of China into the WTO in the late 1990s, which he blames for wrecking the textile business. His family-owned business employed around 3,000 people in the U.S. in 2000, he says. Now that workforce is just 320.

Jay Self, whose family owns Greenwood Mills, says many local voters were turned off to the Democratic Party when President Clinton pushed to get China into the World Trade Organization in the late 1990s. PHOTO: DANIELLE PAUL FOR THE WALL STREET JOURNAL

As with many onetime Democratic manufacturing strongholds, social issues played a role in the shift to red from blue. Rep. Derrick supported the 1993 Brady Bill that mandated background checks on firearms purchases. Angry gun owners packed a town hall meeting in Pickens, S.C. He did not run for re-election in 1994.

Rep. Derrick, who died in 2014, was succeeded by a series of Republicans, all of whom took conservative positions on social issues and opposed the free trade deals unpopular in the district. “Down here, the Democrats shifted their attention to career people like in the medical industry, accountant or lawyers,” Clemson University political scientist David Woodard said. But current factory workers, he said, came from “linthead” families, using the local term for textile workers. “They all love Trump.”

The changing allegiances in factory towns have scrambled politics for both Democrats and Republicans.

Voters for Democrats now tend to be better educated, more urban and less likely to identify themselves as blue-collar than Republicans and Independents, according to pollsters.

As the economic core of metropolitan areas has changed from manufacturing to services, finance and technology, the party has made little room for the conservative cultural views of many blue-collar workers and has embraced gay rights and increased immigration. The 2016 Democratic platform, for instance, had 19 mentions of rights for LGBT people. The 1992 platform had a single mention of the word “gay.”

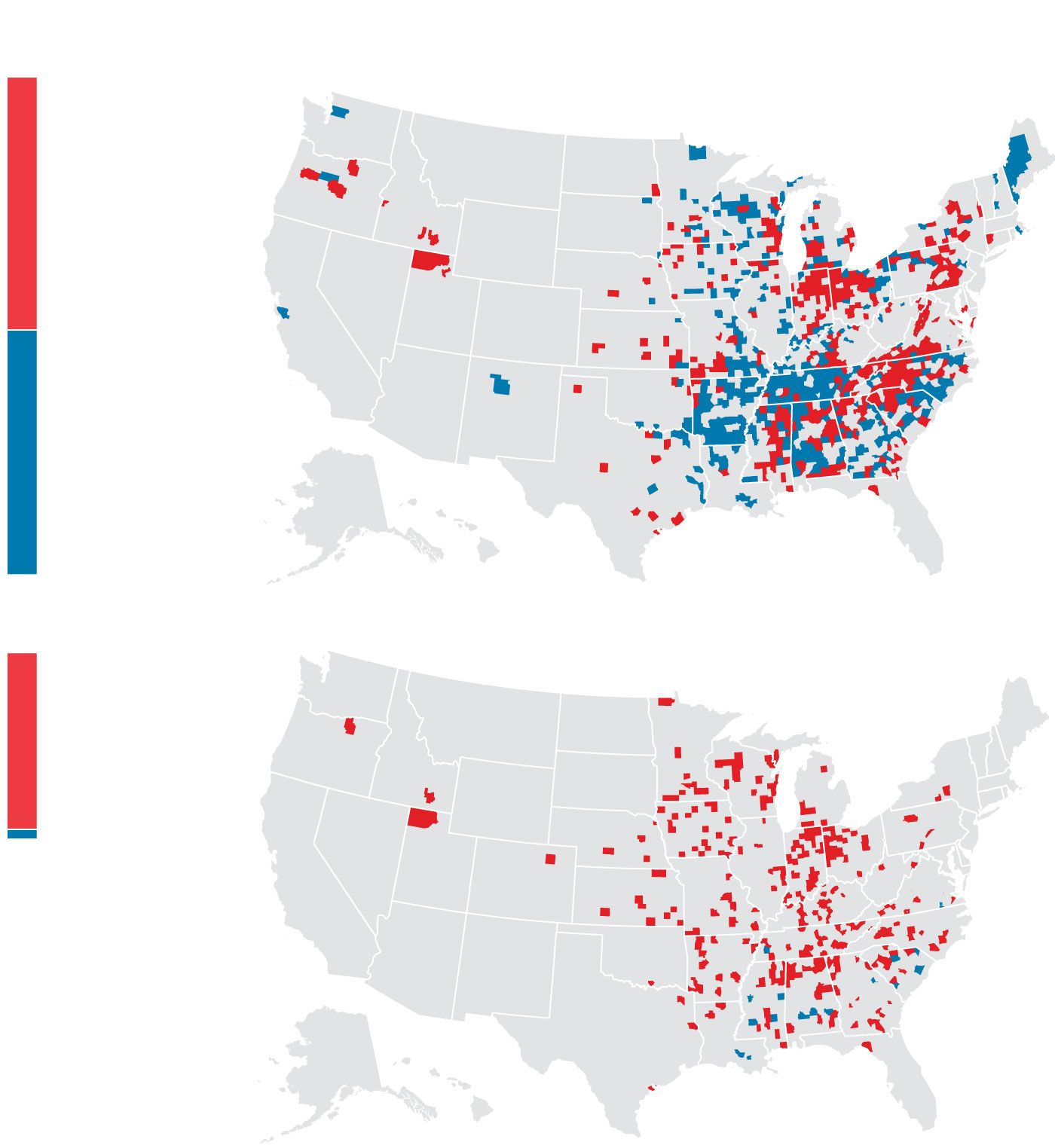

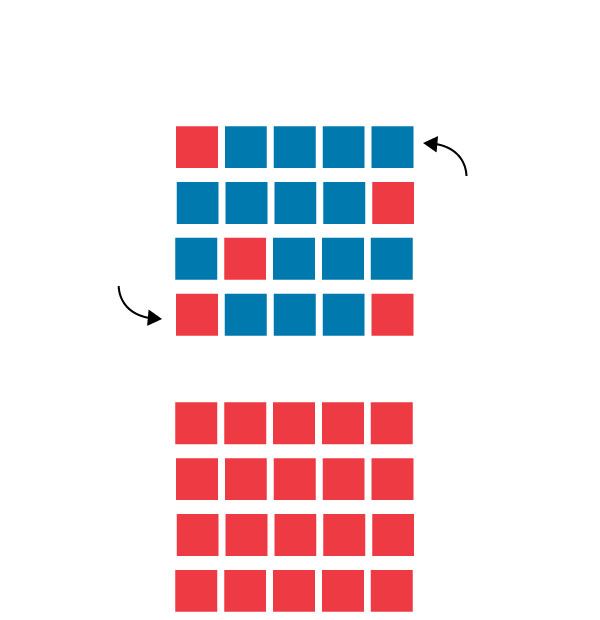

The 20 Congressional districts with the highest share of manufacturing jobs, by election result.

1992

4

3

2

1

5

Democratic district

6

9

10

7

8

Republican district

12

13

14

15

11

18

17

19

16

20

2016

5

4

3

2

1

8

6

9

10

7

14

12

11

13

15

18

17

19

16

20

Sources: U.S. Census Bureau (manufacturing); Dave Leip's Atlas of U.S. Presidential Elections; University of Colorado at Boulder’s Congressional District Data File (election results)

While House Democrats overwhelmingly oppose free-trade deals, their voters don’t. By a 57% to 16% margin, Democrats said that free trade helped the U.S., according to a February 2017 Wall Street Journal/NBC poll, the last one to address this issue.

Republicans, meanwhile, have become more attuned to the desires of manufacturers and their workers. They have led a crackdown on immigration, moved away from plans to privatize Social Security and support some infrastructure spending. Most notably, the party has retreated from free trade.

In 1992, the Republican Party platform declared the GOP the party of “tough free traders” who pushed an expansive “free trade agenda.” In 2016, reflecting Mr. Trump’s presidential candidacy, the platform said instead that the U.S. needed “better negotiated trade agreements that put America first.” The platform coupled “free trade” with “fair trade,” a term that Rust Belt Democrats have long used.

In December 1999, the earliest that The Wall Street Journal/NBC polled on trade issues, Republicans by a 37% to 31% margin said that free trade deals helped the U.S. By February 2017, the results were vastly different. By a 53% to 27% margin, Republicans said free trade hurt the U.S.

Republicans need to hold on to their manufacturing base to retain control of Congress.

The GOP holds a 23-seat majority the House of Representatives. About 50 Congressional districts rated competitive by political analysts have manufacturing workforces higher than the national average. In the Senate, the GOP margin is just two seats, and many big manufacturing states have Senate races this fall, including the states that won Mr. Trump the White House—Michigan, Ohio, Pennsylvania and Wisconsin.

If President Trump’s aggressive trade policy toward China, the European Union and elsewhere resonates, that could put Republicans over the top in these places. If his tariffs—and retaliation—damage local economies, the GOP could find its blue-collar base in a surly mood or apathetic about voting.

Corey Adams works at Staub Manufacturing Solutions in Dayton, Ohio. PHOTO: ANDREW SPEAR FOR THE WALL STREET JOURNAL

Photos of President Donald Trump hang on the wall at Staub Manufacturing. Owner Steve Staub attended the State of the Union address this year as a guest of the president. PHOTO: ANDREW SPEAR FOR THE WALL STREET JOURNAL

Congressional districts hit by big increases in imports have moved to away from the political center, in either direction, according to David Autor, a Massachusetts Institute of Technology economist who studied how import competition affected political affiliation. What linked groups on the left and right was skepticism of free trade.

These changes are evident in Ohio’s eighth Congressional district, long a Republican bastion in the Cincinnati suburbs.

In 1992, the district was represented by Republican John Boehner, the former House speaker. He voted for the North American Free Trade Agreement, and helped pave the way for the Trans-Pacific Partnership, a trade deal among the U.S. and 11 Pacific-Rim nations that Mr. Trump pulled out of on his first workday in office.

From 1990, when Mr. Boehner was elected, to 2015, the percentage of the workforce employed in manufacturing in his district declined from 30% to 21%. It moved up in the ranking of manufacturing intensive districts, from No. 27 to No. 12, because the country’s concentration of manufacturing workers declined even more. General Motors Co. closed a nearby factory in 2008 that employed 2,400 people. NCR Corp. moved its headquarters out of the area in 2009.

Seven area golf courses, long establishment Republican strongholds, have closed since 2012. Without the GM plant, “there is no middle-level management that can afford the dues structure anymore,” said Steve Jurick, executive director of the Miami Valley Golf Association.

Mr. Boehner retired in 2015, as the growing power of populist conservatives in the House made his caucus more difficult to manage. His successor is Republican Warren Davidson, a member of the Freedom Caucus that bedeviled Mr. Boehner.

Congressman Warren Davidson, center, talked to workers at Hartzell Propeller Inc. in Piqua, Ohio. The company manufactures aircraft propellers. PHOTO: ANDREW SPEAR FOR THE WALL STREET JOURNAL

Though he has criticized across-the-board tariffs, he has supported Mr. Trump’s tariffs on Chinese goods. Like Mr. Trump, Mr. Davidson faults the WTO for failing to rein in China, whose imports have battered the district’s many small metal fabrication plants.

At a meeting with local business leaders in May, he likened trade to a basketball game. “They are not calling fouls and no one is taking free throws,” he told the group. “I’m glad President Trump is making them call fouls.”

The message goes over well with factory owners and workers in the district.

“A lot of our workers voted for Trump,” says Neil Douglas, a Democrat who is president of the International Association of Machinists and Aerospace Workers in Middletown, Ohio. “The Democrats around here—sometimes we do feel like the party left us.”

Write to Bob Davis at bob.davis@wsj.com and Dante Chinni at Dante.Chinni@wsj.com

A generation ago, Democrats represented much of the country’s manufacturing base. Now, it’s in GOP hands, a swing remaking both parties

Wayne Wright keeps the fabric flowing at the Harris textile plant owned Greenwood Mills in Greenwood, S.C. DANIELLE PAUL FOR THE WALL STREET JOURNAL

By Bob Davis and Dante Chinni

July 19, 2018 11:16 a.m. ET

WASHINGTON—The Republican Party has become the party of blue-collar America.

After the 1992 election, 15 of the 20 most manufacturing-intensive Congressional districts in America were represented by Democrats. Today, all 20 are held by Republicans.

The shift of manufacturing from a Democratic stronghold to a Republican one is a major force remaking the two parties. It helps explain Donald Trump’s political success, the rise of Republican protectionism and the nation’s polarized politics. It will help shape this year’s midterm elections.

Conservative Takeover

In the 1992 presidential election, manufacturing-intensive counties split pretty evenly between the Democratic and Republican contenders. By 2016, nearly all those counties voted Republican.

Counties where manufacturing is at least 25% of all jobs, by election result

1992

438 Counties that went for George H.W. Bush

424 Counties that went for Bill Clinton

2016

306 Counties that went for Donald Trump

17 Counties that went for Hillary Clinton

Sources: Brookings Institution (manufacturing); Dave Leip's Atlas of U.S. Presidential Elections; University of Colorado Boulder’s Congressional District Data File (election results)

South Carolina’s third Congressional district, on the edge of the Blue Ridge Mountains, epitomizes the swing from blue to red.

In 1992, the district was dotted with textile mills and was represented by a Democrat, Butler Derrick, as it had been for the prior 17 years. He backed gun control, got along with unions and voted for a 1986 law granting citizenship to millions of illegal immigrants.

The district has since become an auto-parts and plastics manufacturing center. Then and now it was among the 20 districts in the nation with the highest concentration of workers in the manufacturing sector, according to a Wall Street Journal analysis of census data.

Today, the district is represented by a Republican, Jeff Duncan. He has compared illegal immigrants to “any kind of vagrant or animal,” gets a 5% rating by the AFL-CIO and derides the World Trade Organization as a “globalist organization” with too much power.

“We’re in servitude” to Chinese bond buyers and other creditors, he told a constituent during a teleconference with voters in May.

Greenwood Mills’ Harris plant produces undyed cloth from bales of cotton and nylon. At the bottom right, Ginger Strawhorn checks the cloth for imperfections. PHOTOS: DANIELLE PAUL FOR THE WALL STREET JOURNAL(3)

The Republican Party didn’t have a grand strategy to capture manufacturing. It happened over time as the economy and party changed.

Many counties that leaned toward Democrats lost so many factory jobs during the past 25 years that they ceased being manufacturing centers.

As the U.S. factory workforce diminished in size—from 15.4% of the U.S. workforce in 1992 to 8.5% today—it moved out of big cities that were union strongholds and into blue-collar suburbs.

Declining SectorManufacturing as a percentage of all jobsSource: Labor Department via the Federal ReserveBank of St. Louis

%1990’952000’05’10’150246810121416

The Northeast and New England, strongholds for Democrats, largely disappeared from the map of manufacturing-intensive counties, according to an analysis for the Journal by the Brookings Institution’s metropolitan policy program. There are no manufacturing-intensive counties any longer in Massachusetts or Connecticut.

Pittsburgh, another Democratic bastion, shed its Steel City heritage and became a university and health-care center. Manufacturing jobs declined by 37,000 in the metropolitan area since 1992, while the number of service-industries employees increased by 168,000.

The new manufacturing heartland runs through areas outside suburbs along interstate highways south from Michigan, Minnesota and Wisconsin through Ohio and into the Carolinas and the deep South.

There, whites without a college education, who identified with the Republican Party’s focus on social issues and abortion restrictions, took up many of the factory jobs. The Trump administration’s tough stance on trade deepened the bonds with workers who believed they were hurt by free-trade deals.

“Manufacturing moved to where the Republican party has been building strength,” says Jonathan Rodden, a Stanford University political scientist, who studies the geography of political change.

Other manufacturing areas have flipped to vote for Republicans. In 1992, there were 860 counties where at least 25% of the working population was employed in manufacturing. Democrat Bill Clinton won 49% of those counties. By 2016, manufacturers employed at least a quarter of the workforce in only 320 counties. Ninety-five percent of them went for Donald Trump.

Hartzell Propeller Inc. in Piqua, Ohio, manufactures propellers for aircrafts. Baline Collins, top, is a new hire. Jeff Newnam, lower right, has worked at the company for 37 years. PHOTOS: ANDREW SPEAR FOR THE WALL STREET JOURNAL(3)

In Wisconsin, five manufacturing-intensive counties in the northwest of the state have flipped from Democrats to Republicans since 1992. Three of those counties went for Mr. Trump in 2016 by margins of more than 25 percentage points.

Labor unions, which have long allied with Democrats, now represent just 9% of manufacturing workers, down from 20% in 1992, according to Barry Hirsch, an economist at Georgia State University.

“My image of Republicans is of a blue-collar type,” says Larry Smith, a 68-year-old weave room supervisor at Greenwood Mills Inc. in South Carolina’s third Congressional District. He voted for Democrats before, including Barack Obama in 2008, but sided with Mr. Trump in 2016. “Democrats come from more financially successful groups.”

His boss, Jay Self, says a lot of local voters were turned off to the Democratic Party when Bill Clinton eased the entry of China into the WTO in the late 1990s, which he blames for wrecking the textile business. His family-owned business employed around 3,000 people in the U.S. in 2000, he says. Now that workforce is just 320.

Jay Self, whose family owns Greenwood Mills, says many local voters were turned off to the Democratic Party when President Clinton pushed to get China into the World Trade Organization in the late 1990s. PHOTO: DANIELLE PAUL FOR THE WALL STREET JOURNAL

As with many onetime Democratic manufacturing strongholds, social issues played a role in the shift to red from blue. Rep. Derrick supported the 1993 Brady Bill that mandated background checks on firearms purchases. Angry gun owners packed a town hall meeting in Pickens, S.C. He did not run for re-election in 1994.

Rep. Derrick, who died in 2014, was succeeded by a series of Republicans, all of whom took conservative positions on social issues and opposed the free trade deals unpopular in the district. “Down here, the Democrats shifted their attention to career people like in the medical industry, accountant or lawyers,” Clemson University political scientist David Woodard said. But current factory workers, he said, came from “linthead” families, using the local term for textile workers. “They all love Trump.”

The changing allegiances in factory towns have scrambled politics for both Democrats and Republicans.

Voters for Democrats now tend to be better educated, more urban and less likely to identify themselves as blue-collar than Republicans and Independents, according to pollsters.

As the economic core of metropolitan areas has changed from manufacturing to services, finance and technology, the party has made little room for the conservative cultural views of many blue-collar workers and has embraced gay rights and increased immigration. The 2016 Democratic platform, for instance, had 19 mentions of rights for LGBT people. The 1992 platform had a single mention of the word “gay.”

The 20 Congressional districts with the highest share of manufacturing jobs, by election result.

1992

4

3

2

1

5

Democratic district

6

9

10

7

8

Republican district

12

13

14

15

11

18

17

19

16

20

2016

5

4

3

2

1

8

6

9

10

7

14

12

11

13

15

18

17

19

16

20

Sources: U.S. Census Bureau (manufacturing); Dave Leip's Atlas of U.S. Presidential Elections; University of Colorado at Boulder’s Congressional District Data File (election results)

While House Democrats overwhelmingly oppose free-trade deals, their voters don’t. By a 57% to 16% margin, Democrats said that free trade helped the U.S., according to a February 2017 Wall Street Journal/NBC poll, the last one to address this issue.

Republicans, meanwhile, have become more attuned to the desires of manufacturers and their workers. They have led a crackdown on immigration, moved away from plans to privatize Social Security and support some infrastructure spending. Most notably, the party has retreated from free trade.

In 1992, the Republican Party platform declared the GOP the party of “tough free traders” who pushed an expansive “free trade agenda.” In 2016, reflecting Mr. Trump’s presidential candidacy, the platform said instead that the U.S. needed “better negotiated trade agreements that put America first.” The platform coupled “free trade” with “fair trade,” a term that Rust Belt Democrats have long used.

In December 1999, the earliest that The Wall Street Journal/NBC polled on trade issues, Republicans by a 37% to 31% margin said that free trade deals helped the U.S. By February 2017, the results were vastly different. By a 53% to 27% margin, Republicans said free trade hurt the U.S.

Republicans need to hold on to their manufacturing base to retain control of Congress.

The GOP holds a 23-seat majority the House of Representatives. About 50 Congressional districts rated competitive by political analysts have manufacturing workforces higher than the national average. In the Senate, the GOP margin is just two seats, and many big manufacturing states have Senate races this fall, including the states that won Mr. Trump the White House—Michigan, Ohio, Pennsylvania and Wisconsin.

If President Trump’s aggressive trade policy toward China, the European Union and elsewhere resonates, that could put Republicans over the top in these places. If his tariffs—and retaliation—damage local economies, the GOP could find its blue-collar base in a surly mood or apathetic about voting.

Corey Adams works at Staub Manufacturing Solutions in Dayton, Ohio. PHOTO: ANDREW SPEAR FOR THE WALL STREET JOURNAL

Photos of President Donald Trump hang on the wall at Staub Manufacturing. Owner Steve Staub attended the State of the Union address this year as a guest of the president. PHOTO: ANDREW SPEAR FOR THE WALL STREET JOURNAL

Congressional districts hit by big increases in imports have moved to away from the political center, in either direction, according to David Autor, a Massachusetts Institute of Technology economist who studied how import competition affected political affiliation. What linked groups on the left and right was skepticism of free trade.

These changes are evident in Ohio’s eighth Congressional district, long a Republican bastion in the Cincinnati suburbs.

In 1992, the district was represented by Republican John Boehner, the former House speaker. He voted for the North American Free Trade Agreement, and helped pave the way for the Trans-Pacific Partnership, a trade deal among the U.S. and 11 Pacific-Rim nations that Mr. Trump pulled out of on his first workday in office.

From 1990, when Mr. Boehner was elected, to 2015, the percentage of the workforce employed in manufacturing in his district declined from 30% to 21%. It moved up in the ranking of manufacturing intensive districts, from No. 27 to No. 12, because the country’s concentration of manufacturing workers declined even more. General Motors Co. closed a nearby factory in 2008 that employed 2,400 people. NCR Corp. moved its headquarters out of the area in 2009.

Seven area golf courses, long establishment Republican strongholds, have closed since 2012. Without the GM plant, “there is no middle-level management that can afford the dues structure anymore,” said Steve Jurick, executive director of the Miami Valley Golf Association.

Mr. Boehner retired in 2015, as the growing power of populist conservatives in the House made his caucus more difficult to manage. His successor is Republican Warren Davidson, a member of the Freedom Caucus that bedeviled Mr. Boehner.

Congressman Warren Davidson, center, talked to workers at Hartzell Propeller Inc. in Piqua, Ohio. The company manufactures aircraft propellers. PHOTO: ANDREW SPEAR FOR THE WALL STREET JOURNAL

Though he has criticized across-the-board tariffs, he has supported Mr. Trump’s tariffs on Chinese goods. Like Mr. Trump, Mr. Davidson faults the WTO for failing to rein in China, whose imports have battered the district’s many small metal fabrication plants.

At a meeting with local business leaders in May, he likened trade to a basketball game. “They are not calling fouls and no one is taking free throws,” he told the group. “I’m glad President Trump is making them call fouls.”

The message goes over well with factory owners and workers in the district.

“A lot of our workers voted for Trump,” says Neil Douglas, a Democrat who is president of the International Association of Machinists and Aerospace Workers in Middletown, Ohio. “The Democrats around here—sometimes we do feel like the party left us.”

Write to Bob Davis at bob.davis@wsj.com and Dante Chinni at Dante.Chinni@wsj.com